On "Learning DDD"

I finished reading Vlad Khononov’s Learning Domain Driven Design yesterday. This is the second book by this author that I picked up, after Balancing Coupling in Software Design, which I dropped midway through.

This book is in many ways similar to Balancing Coupling…, in that the form that it follows is pretty much exactly the same. Unfortunately, it is a form that very much does not land for me. Khononov’s books are in my opinion basically unreadable as books, even though they have a lot of good information. The problem is with how this information is presented.

Perhaps I am spoiled by John Ousterhout and his excellent A Philosophy of Software Design, which has experimental support for its theses, and the software projects there act like characters in a novel. By contrast, both of the Kononov’s books essentially amount to enumerations of concepts, often thought up by someone else, that have been curated, and brought into a context of a completely arbitrary and theoretical system that is so generic that you forget it the moment you turn the page. However, once you reach Chapter 14, you’re expected to remember the definition of a term introduced in Chapter 3 and never mentioned again throughout the book, without which the entire thing doesn’t make sense.

This is even more frustrating by the addition of an Appendix, that describes the way the concepts presented in the books have been used in a real-world scenario. Personally, I would have expected these concepts and experiences to be woven throughout the book, rather than using abstract and highly generic business domains, in order to bring up some more relatable understanding for the reader.

The “enumeration of concepts” style was the reason why I dropped Balancing Coupling…—I had neglected to take notes, and by part three of the book I barely understood what the references were to. This time I was a little bit wiser, and having already familiarised myself with the style of this author, I began taking copious notes.

Roughly midway through reading the book I made a list of questions that I felt hadn’t been sufficiently explained by that point. These questions mainly concerned concurrency, database transactionality, coordination between aggregates, serialising and deserialising the domain model and ubiquitous language changes.

The questions of database transactionality and coordination between aggregates were explained later, and I have no qualms here. The topic of concurrency has been treated very superficially. In the latter chapters there is discussion on the subject of distributed systems, but the matter of concurrency specifically is not really touched upon. Perhaps it was a disciplined move to avoid introducing such a complex topic into an already rather dense book, but it might as well be the case that the matter of concurrency would be treated ad-hoc, when it arises, as it often does in object-oriented systems (the code listings in the book are in, I believe, C#).

It’s regrettable that the matter of data persistence in event-sourced systems is not touched upon, because it feels like the transition from a state-based system (implemented with the transaction script or active record patterns) to a full-fledged event-sourced domain model deserves some explanation of how to actually implement it database-wise. There are ways to dip one’s toes into event sourcing without going all the way (for example by using the criminally underrated prevalent system), so it would be nice to show a stepping stone between the approaches.

Finally, the most frustrating problem of DDD, which in my opinion changing ubiquitous language certainly is, is not really addressed beyond a single acknowledgment. Once again I suspect this might be because C# is a mature language with advanced tooling, in which renaming a symbol across an entire codebase is not complicated, but in languages such as JS or Elixir, the mere change of a term used to describe a certain domain entity causes difficult to explain tech-debt tasks with high estimations. In a piece of software that I worked on in the biotech domain, the changing of the core business domain term “experiment” to “[clinical] study” took about two weeks to propagate through the code- and database. Not an easy thing to justify to the stakeholders.

That said, is this a good book? Is it worth reading?

I would say that the best parts are the first four or five chapters introducing the core concepts of DDD, which is here done much better than in the seminal Eric Evans’s blue book. Then, I would suggest skipping to chapter 12, which details event storming. Finally, the best part of the book is without a doubt the Appendix, which indeed has a lot of useful advice on how DDD can be implemented in a real-world scenario—I only wish more such cases were related throughout the rest of the book.

Notes

Domain identification

- Core subdomains are “what a company does.” They are the source of competitive advantage.

- According to the book, they are unlikely to be outsourced. This is not the case in my experience—many enterprises may be willing to outsource the implementation of the core subdomain to a competent team of consultants, because they cannot afford to do it wrong.

- Generic subdomains don’t provide inherent competitive advantage. It’s better to go with a battle-tested solution here.

- The idea of using something custom for ATS or e-commerce is difficult to justify, especially if it’s vibe-coded and potentially unreliable.

- Supporting subdomains are unique to the business but do not provide competitive advantage on their own (e.g. internal tools unique to the business).

- When business domain experts don’t work directly with engineers, but instead the knowledge is pushed through an intermediate layer of analysts, it’s likely that knowledge is being lost.

- As such, a BA is not a middle layer; it’s more like a cache—someone who can serve as a supporting role for when engineers for some reason can’t sort out the requirements themselves.

Ubiquitous language

- Domain experts must be comfortable using the ubiquitous language to reason about their own business domain.

- Ubiquitous language is the cornerstone practice of DDD.

- It is often thought as the domain experts enforcing their language on the engineering team. But, conversely, we as programmers have the power to introduce ubiquitous language to the domain so that domain experts gain new understanding and maintain consistency.

Bounded contexts

- When different domain experts have conflicting views of the domain, we can reconcile them by introducing bounded contexts.

- Bounded contexts are essentially semantic domains plus ownership; a context should be owned by one team.

- They are effectively arbitrary, but should at least in some way reflect the business communication model.

- A “product” might be a different thing for marketing, sales, and fulfillment. At the point where marketing considers a product, it might not even be on the shelf.

- Different bounded contexts can represent the same business entities but model them differently to solve different problems.

- Bounded contexts can create interactions between each other called contracts; they represent how different contexts rely on one another.

- Broad kinds of contracts:

- Partnership: contexts are integrated ad hoc; requires very good communication between the teams.

- Shared kernel: two or more contexts are integrated by sharing a limited overlapping model that belongs to all bounded contexts; goes against the principle that a context should be owned by only one team.

- Conformist: the consumer conforms to the service provider’s model; used if the downstream is willing to accept the upstream model.

- Anti-corruption layer (ACL): consumer translates the provider’s model in a way that fits its needs.

- Open host system (OHS): provider creates a published language that is different from the language used internally but is closer to what the customers expect and use—a model optimized for its consumers’ needs.

- Separate ways: it’s less expensive to duplicate particular functionality than to collaborate and integrate it.

- Use context map to plot the structure of contexts to gain insight into high-level communication patterns (contextmapper.org).

- Broad kinds of contracts:

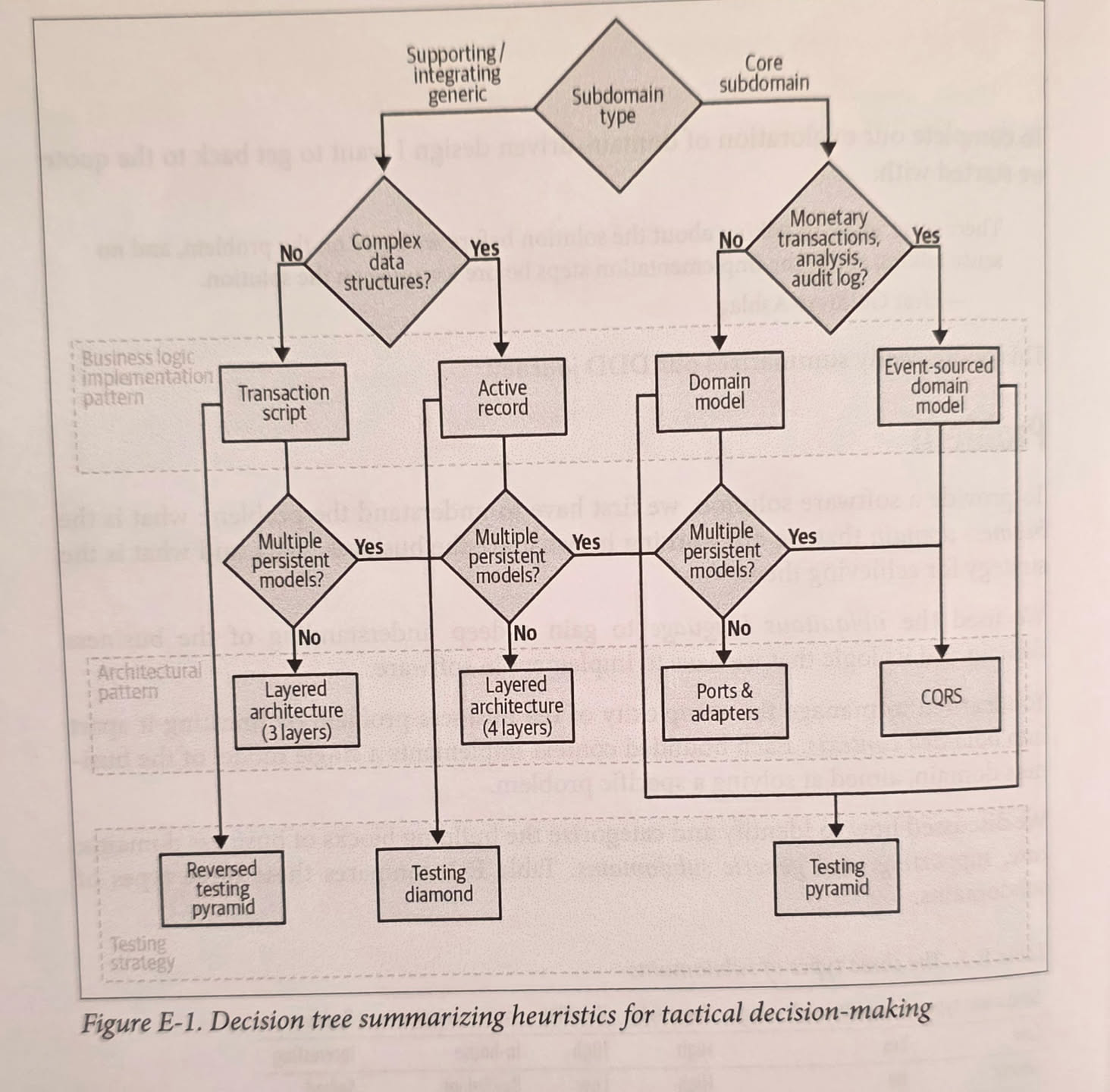

Business logic patterns

- Transaction script: can be called from the UI via some kind of RPC; unlimited capabilities; can access DB or do whatever it likes, but the requirement is that it doesn’t leave the system in an invalid state.

- Active record: object representing a row in the database that can be manipulated in memory and then committed at once; mostly OOP nonsense; changesets are superior in almost every way because they preserve the list of changes and also can handle validation more gracefully.

- Domain model pattern:

- Used for much more complex tasks, so that it captures all the aspects of the domain requirements.

- Avoids accidental complexity; uses mostly plain objects, single thread, and pure functions.

- The names in the code should correspond to ubiquitous language.

Building blocks of the domain model

- Value objects: objects whose identity corresponds to their values (if a value object has “multiple values,” i.e., is a product type like RGB color, then identity is considered on the product as a whole).

- If value objects consist of multiple fields, they should avoid the “primitive obsession” code smell and use type aliases that are properly validated on their fields (e.g., a type

userconsisting of a name and an email shouldn’t bestring * stringbut some actual constructed typesname * emailthat have some kind of parsing logic in their construction). - Value objects should be immutable and should have proper equality checks implemented.

- Examples: money, RGB colors, addresses.

- If value objects consist of multiple fields, they should avoid the “primitive obsession” code smell and use type aliases that are properly validated on their fields (e.g., a type

- Entities: objects whose identity is explicit (typically by an ID field).

- Entity ID should be immutable—other aspects of the entity might change but not the ID.

- Aggregates: entities that enforce consistency.

- An entity that is something like a state machine—external callers are only allowed to read the aggregate state, and any modifications must be done through the public interface and be internally consistent/transactional.

- Conversely, an update to multiple aggregates must not be transactional.

- To decide if an entity belongs to an aggregate, examine whether the aggregate contains business logic that can lead to an invalid system state if it works with eventually consistent data.

- Aggregates can and should create and publish domain events, which are events that describe changes in the system state and can be subscribed to and responded to.

- Modelling the domain with events has the advantage of events being more lasting—a company might do the same thing for 20 years and have the same events, but the object structure in OO modelling might change before even the first deploy.

- Domain services: orchestrate calls to aggregates when strong consistency is not a requirement.

- Domain services lend themselves to implementing logic that requires reading data from multiple aggregates.

Event-sourced domain model

- Event log is an append-only storage that preserves all business events logged from aggregates, and we use projections to create read models from the event log.

- How do we deal with exceedingly large event logs?

- Event-sourced domain model uses domain events for modelling the aggregates’ life cycles. All changes to an aggregate state have to be expressed as domain events.

- The most significant disadvantage of event sourcing is that evolving the model and changing the schema of events is very hard (Young, Versioning in an Event Sourced System).

- Also: a lot of moving parts.

- Event sourcing can scale because the events include aggregate ID, which lends itself to sharding by it.

Architecture

- Layered architecture: horizontal layers—UI, controllers, data access.

- Ports & adapters: reverse the arrows—business logic doesn’t depend on anything but exposed interfaces that application and data access layers have to implement.

- CQRS:

- The idea is that we have a database that we commit our writes to, and then in an eventually consistent way that is projected to other data sources like Elasticsearch or Redis.

- The value proposition is that your projections can be radically different shapes than your write model. Not just “denormalized for performance” but genuinely different—your write model might be fine-grained aggregates enforcing business rules, while your read model is pre-joined, pre-computed views shaped for specific screens. Whether that’s worth the eventual consistency headache depends entirely on whether maintaining a single model is actually causing you pain.

- OLTP: lots of small, fast operations, ACID transactions. OLAP: complex joins across millions of rows.

- A command can only operate on the strongly consistent command execution model.

- Commands should return data (common misconception): validation data, failure states, updated records from the strongly consistent model.

- In FP world, a command can be something that returns a new, modified entity.

- Architecture decisions should be made on individual vertical slices of the bounded context, not necessarily made for the entire system. Some slices of the system might have different needs, and we can scope them individually better.

- This is a very important point worth emphasizing: event sourcing is often thought of as all or nothing, but it doesn’t have to be. The event-sourced model can be used sparingly in places that really need it.

Communication patterns

- Outbox: events are saved atomically with a change to an outbox table, which is periodically polled or uses notifications to publish domain events.

- Saga: multiple transactions that are a part of the same long-running business process.

- Process manager: to be honest, I didn’t understand it.

- Unregulated growth that leads to big balls of mud results from extending a software system’s functionality without re-evaluating its design decisions.

Event storming

- Event storming:

- EventStorming is a low-tech activity for a group of people to rapidly model a business process.

- Before the session, a scope should be agreed upon.

- Usually a session is conducted in 10 steps:

- Unstructured exploration: brainstorming domain events. Events are things that happen to the business, formulated in past tense.

- Timelines: happy path scenario first; order domain events in a timeline. The timeline can branch in case there are exceptional cases to handle. Fix incorrect events, remove duplicates, and add missing events if necessary.

- Pain points: identify parts of the process that require attention (bottlenecks, manual steps that require automation, missing documentation, missing domain knowledge).

- Pivotal events: find significant events that indicate a change in context or phase. Pivotal events are an indicator of potential bounded context boundaries.

- Commands: commands describe what triggered the event, formulated in the imperative, placed before events that they produce. If a command is executed by a particular actor, the actor information is added next to the command.

- Policies: when commands have no actor that triggers them directly but are triggered because of an event, we are dealing with an automation policy. Policies connect events to commands.

- Read model: a view of the data within the domain that the actor uses to make a decision to execute a command. This can be a system screen, a report, a notification.

- External systems: any system that is not part of the domain being explored. It can execute commands or be notified about events (e.g., a CRM).

- Aggregates: once all the events and commands are represented, the participants can start thinking about organizing related concepts in aggregates. Aggregates receive commands and produce events.

- Bounded contexts: the last step is to look for aggregates that are related to each other because they represent related functionality or because they are coupled through policies.

- Steps 1–4 are the best to get a broad understanding of the domain and hash out the ubiquitous language that the team will use.

- Besides exploring new business requirements, EventStorming can also be used to recover domain knowledge in legacy systems.

DDD in the real world

- The best projects that have the most opportunity to benefit from DDD are those that have already proven their business viability and need a shakeup to fight accumulated technical debt and design entropy.

- Fundamentally, real-world DDD adoption is about reconciling the business language and domain with the technical practice of the developers.

Microservices

- The idea of a service is that it’s an encapsulated capability with a defined interface. A microservice is therefore something with a micro-interface.

- Admittedly, in a service-oriented architecture monoliths, internal services are much smaller than “microservices” that have come to be understood as Docker containers, so the naming is a bit weird here.

- Theoretically we could fight high local complexity by only making small services that implement a single method and are otherwise inaccessible to the outside world. But if these nanoservices were to encapsulate their database, we would have to implement “staff only” methods for other nanoservices to synchronize their data.

- We trade having almost no local complexity for having a huge amount of global complexity.

- It seems like the idea in the book is that we should design services to straddle the balance between local and global complexity.

- Namedropped Ousterhout and A Philosophy of Software Design—the idea behind module depth. Microservices should be deep modules.

- The idea behind module depth is pretty simple: picture a module as a rectangle, with “the internal complexity” being the area and “size of the public interface” being the top edge. A module is deep when it encapsulates a lot of internal complexity behind a relatively small public interface—when the rectangle is tall but narrow.

- Shallow services are indicated as the reason why microservices projects fail.

- The edges of bounded contexts and microservices don’t align—services should be larger than the contexts.

- Bounded contexts denote the boundaries of the largest valid monolith.

- Aggregates, on the other hand, denote the boundaries of the smallest possible microservice.

- Subdomains are natural boundaries of microservices because they can be naturally deep. But there might be nonfunctional requirements that suggest smaller size (down to aggregate) or functional requirements that’d make expanding to a larger bounded context more preferable.

Event-driven architecture

- EDA is an architectural pattern that makes services communicate with each other via published and subscribed events rather than with procedure calls.

- Event sourcing and EDA are unrelated because event sourcing happens in the service, while EDA is a pattern of communication between services.

- In EDA there are two types of messages: events and commands.

- Command is a message describing an operation to be carried out. They can be refused to execute, e.g., if validation fails.

- Events describe things that already happened and cannot be refused—the most that can be done is issuing a compensating action (e.g., another command, as in the saga pattern).

- Events further subdivide into three kinds:

- Event notification: small message that indicates that a certain change in a business domain occurred (e.g., an entity was created). Doesn’t contain all the information needed to react to the event, but carries a link where interested subscribers can find out more (often behind further authorization). Example:

{:marriage-recorded, person_id}. - Event-carried state transfer (ECST): notify the subscribers about changes in producer’s internal state. ECST messages may include the complete snapshot of the producer’s internal state. ECST messages should provide sufficient information to hold a local cache of the producer’s data. Example:

{:personal-details-changed, [new_last_name: ...]}. - Domain events: convey information about a change in the business domain, but unlike event notifications aren’t meant for communicating with other services, but modelling the business domain. Example:

{:married, person_id, [assumed_partners_name: true]}.

- Event notification: small message that indicates that a certain change in a business domain occurred (e.g., an entity was created). Doesn’t contain all the information needed to react to the event, but carries a link where interested subscribers can find out more (often behind further authorization). Example:

- Heuristics:

- Use the outbox pattern to publish messages reliably.

- When publishing messages, ensure that the subscribers will be able to deduplicate and reorder messages.

- Leverage the saga pattern when orchestrating cross-context processes.

- Consider consistency:

- If eventually consistent data is okay, use ECST.

- If strong consistency is required: event notification followed up by direct query.

Data mesh

- Operational vs. analytical model (OLTP vs OLAP):

- Operational model is used to record transactions in near-real time. Small writes, small reads, must be fast.

- Analytical model is used to gather information from a longer period of time from the operational model to make business decisions: complex queries with many joins on aggregated data, but rare.

- Data management patterns:

- Data warehouse: ETL scripts that take information from the outside world, transform it into the analytical model, and load it into the database. The problem is that you need to understand the whole enterprise ahead of time to create solid ETL scripts.

- Data lake: schemaless; ingestion is not transformed; the events from the operational system are preserved in their original form at first, and then reworked into individual analytical models for different needs. The problem here is that getting meaningful data out is a lot of work and requires very deep understanding of the business.

- Data mesh: instead of building a monolithic model, use multiple analytical models with bounded context boundaries so that the same team is responsible for the transactional and analytical models.